"Arguing on the internet is like running in the Special Olympics: Even if you win you're still retarded." --- Jesse Dane

Christmas Sucked Ass

But lest anyone return to their dreary cubicle and re-take his (or her) rightful position as worker drone this morning, read my pre-Christmas post and suspect I may have offed myself (or secretly wished it) no such luck, fuckers. Everything's fine. The Hellcat managed to pull it together and we had a quiet, low-key afternoon and night. I made a brunch that was simple and quite tasty. We split a bottle of wine in the evening and managed to find a cute little gay-ish restaurant in Chelsea that was open. Apple martinis and bellinis acompanied a very delicious dinnner. We rested at home and then headed out into the wilds of the East Village for a minor bar tour. The Hellcat got his cock sucked in the bathroom at Urge. And I only bought him dinner. Ah well, next year I'll know. Felize Navi-spooge!

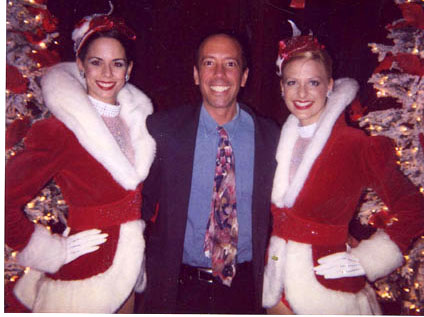

Today I managed to send myself via e-mail the picture I was going to use for my Christmas card. Me and The Rockettes. My hair has grown considerably since then. My concentration camp look will soon be a thing of the past. We just returned from seeing Finding Neverland. I loved it but I cried like a woman.

But lest anyone return to their dreary cubicle and re-take his (or her) rightful position as worker drone this morning, read my pre-Christmas post and suspect I may have offed myself (or secretly wished it) no such luck, fuckers. Everything's fine. The Hellcat managed to pull it together and we had a quiet, low-key afternoon and night. I made a brunch that was simple and quite tasty. We split a bottle of wine in the evening and managed to find a cute little gay-ish restaurant in Chelsea that was open. Apple martinis and bellinis acompanied a very delicious dinnner. We rested at home and then headed out into the wilds of the East Village for a minor bar tour. The Hellcat got his cock sucked in the bathroom at Urge. And I only bought him dinner. Ah well, next year I'll know. Felize Navi-spooge!

Today I managed to send myself via e-mail the picture I was going to use for my Christmas card. Me and The Rockettes. My hair has grown considerably since then. My concentration camp look will soon be a thing of the past. We just returned from seeing Finding Neverland. I loved it but I cried like a woman.

Happy Holidays

Darkness All Around

Yesterday was a dark day. It rained. It was raining when I woke up. It rained on my way to the grocery store and the gym. It poured on my way to the laundry. Great, wind-whipped sheets of rain lashed the streets. I managed to duck under an awning and was luckily wearing a raincoat, but my shoes and socks were soaked and the water managed to seep down my neck and collar. Even the few times I went outside to find it not raining, within a half-block of my walking anywhere, the rain began again. I never could decide if my mood was reflecting the weather, or if the planet was responding to the foul mood I was in.

I was supposed to be getting ready for Christmas. I had started with good intentions. Over morning coffee, I opened the half-dozen Christmas cards I had received the past couple of weeks. I like to open them all at once close to Christmas. It usually pushes me into a good mood but this year, not so much. The fact that some people insist on sending out overtly religious Christmas cards annoys me. I mean, I'm aware that the roots of Christmas are obviously a Christian holiday, but many people, me included, choose to celebrate Christmas as a way to spend time with friends and family, to enjoy good food and good company. To reflect on how fortunate we are to be healthy, safe, and with a place to call home. It's about a gift freely given, a chance to tell a valued friend he is cared for. The religious part of the holiday doesn't interest me. So I find Christmas cards with great, thunderous, biblical quotations, complete with exclamation points, to be an affront. What's wrong with a card that says "Wishing you the warmest of holiday memories" and a beautiful picture of a family in the woods atop a horse-drawn carriage?

Not that I'm really celebrating this year anyway. I can't go home. That's the nightclub business. I have to close tonight. I have Christmas Day off tomorrow, though. No real plans for a party. The Ex left this morning for five days in Buffalo. We didn't exchange gifts for the first time in several years. Not surprising, we've had a rough time in our relationship this year. And no great loss, either. The Ex is a notoriously bad gift giver. He's one of those people that buys you what he thinks you should have instead of what you will like. Last year it was tacky gold jewelry I wouldn't be caught dead wearing and clothes. Size large. I weigh 147 pounds.

So that leaves me, Colby and The Hellcat in town and at home. That relationship has been strained of late as well. The Hellcat attempted what amounted to an out-patient rehab. It consisted of a single visit to a psychiatrist and another to a grief therapist and a plan to attend a month of 12-step programs every day. Alcohol, Drugs, even Sex-Anon, it didn't matter. As the current line of thinking for some people that specialize in addiction is that most people are cross-addicted. With the drugs leading to sex or the alcohol leading to drugs. Also, he went on medication to treat what's believed to be a bi-polar disorder. At any rate, he didn't make it two weeks. I think it was only one night back on the pipe but I can't be sure. So we endured four days of the after-affects. He holes up in his room and sleeps or watches television. He rarely eats and when he does it's junk food or cereal. Walking the dog falls by the wayside. So whenever the dog is left alone in any room besides the bedroom he sleeps in, not surprisingly he shits or pisses. How special is it to come home from work at 2:30 in the morning and have to clean up two or three piles of dogshit? Very special indeed.

After a couple of days gone to ground, The Hellcat will emerge from the bedroom completely manic. He will have worked out yet another theory as to why the rehab didn't take and how the next time will be different. He will follow you from room to room talking incessantly about himself and his problems. Any attempt to change the subject or inject yourself into the conversation will be deflected or ignored, so the subject can once again be all about him. This condition will last a half day or more, at which point he finally exhausts himself so much that another day and a half of laying on the couch and falling asleep to HBO ensues.

This is the time when the cycle begins again. I can usually look forward to a solid week or more of "good" Hellcat, where we can take in a movie or work out together. But lately that's become bittersweet for me too. This is always followed by a week or two where you can see the old patterns of addiction take hold. Now that I've mastered his cycle, in the back of my mind I'm always thinking of what's to come, and trying to figure out the best way to make it affect me and my life the least.

The upshot is that we have tentative plans to whip up a tasty brunch in the afternoon. I've offered to treat him to Christmas dinner at a restaurant of his choosing. Public Assistance doesn't provide him with a Christmas bonus. But this is all predicated on whether or not he can get up and get dressed. I may just be spending Christmas alone. Which I've done before, but for some reason, this alone feels really alone.

I'll probably try and treat it like any other day and ignore it best I can. The Ex is complaining of computer problems so maybe I'll clean up his system for him. A lot of places will be closed, but the diners will be open for food. Movie theaters do a decent business Christmas night. Maybe I'll troll the bars for a lost tourist to take home and unwrap.

I'm sorry this post is such a downer. I could have written a goopy post full of good cheer and love for all humanity. I have it in me. But that's not my reality right now. I wanted to write the truth, and I actually feel a bit better getting it all down "on paper". So, thanks for listening. And I do wish you all the happiest of holidays. If you find yourself lucky enough to be in the presence of good friends and loving family, take a moment to mark it, and thank the Universe for your good fortune. Fear not, we must endure the darkness to truly enjoy the light.

Yesterday was a dark day. It rained. It was raining when I woke up. It rained on my way to the grocery store and the gym. It poured on my way to the laundry. Great, wind-whipped sheets of rain lashed the streets. I managed to duck under an awning and was luckily wearing a raincoat, but my shoes and socks were soaked and the water managed to seep down my neck and collar. Even the few times I went outside to find it not raining, within a half-block of my walking anywhere, the rain began again. I never could decide if my mood was reflecting the weather, or if the planet was responding to the foul mood I was in.

I was supposed to be getting ready for Christmas. I had started with good intentions. Over morning coffee, I opened the half-dozen Christmas cards I had received the past couple of weeks. I like to open them all at once close to Christmas. It usually pushes me into a good mood but this year, not so much. The fact that some people insist on sending out overtly religious Christmas cards annoys me. I mean, I'm aware that the roots of Christmas are obviously a Christian holiday, but many people, me included, choose to celebrate Christmas as a way to spend time with friends and family, to enjoy good food and good company. To reflect on how fortunate we are to be healthy, safe, and with a place to call home. It's about a gift freely given, a chance to tell a valued friend he is cared for. The religious part of the holiday doesn't interest me. So I find Christmas cards with great, thunderous, biblical quotations, complete with exclamation points, to be an affront. What's wrong with a card that says "Wishing you the warmest of holiday memories" and a beautiful picture of a family in the woods atop a horse-drawn carriage?

Not that I'm really celebrating this year anyway. I can't go home. That's the nightclub business. I have to close tonight. I have Christmas Day off tomorrow, though. No real plans for a party. The Ex left this morning for five days in Buffalo. We didn't exchange gifts for the first time in several years. Not surprising, we've had a rough time in our relationship this year. And no great loss, either. The Ex is a notoriously bad gift giver. He's one of those people that buys you what he thinks you should have instead of what you will like. Last year it was tacky gold jewelry I wouldn't be caught dead wearing and clothes. Size large. I weigh 147 pounds.

So that leaves me, Colby and The Hellcat in town and at home. That relationship has been strained of late as well. The Hellcat attempted what amounted to an out-patient rehab. It consisted of a single visit to a psychiatrist and another to a grief therapist and a plan to attend a month of 12-step programs every day. Alcohol, Drugs, even Sex-Anon, it didn't matter. As the current line of thinking for some people that specialize in addiction is that most people are cross-addicted. With the drugs leading to sex or the alcohol leading to drugs. Also, he went on medication to treat what's believed to be a bi-polar disorder. At any rate, he didn't make it two weeks. I think it was only one night back on the pipe but I can't be sure. So we endured four days of the after-affects. He holes up in his room and sleeps or watches television. He rarely eats and when he does it's junk food or cereal. Walking the dog falls by the wayside. So whenever the dog is left alone in any room besides the bedroom he sleeps in, not surprisingly he shits or pisses. How special is it to come home from work at 2:30 in the morning and have to clean up two or three piles of dogshit? Very special indeed.

After a couple of days gone to ground, The Hellcat will emerge from the bedroom completely manic. He will have worked out yet another theory as to why the rehab didn't take and how the next time will be different. He will follow you from room to room talking incessantly about himself and his problems. Any attempt to change the subject or inject yourself into the conversation will be deflected or ignored, so the subject can once again be all about him. This condition will last a half day or more, at which point he finally exhausts himself so much that another day and a half of laying on the couch and falling asleep to HBO ensues.

This is the time when the cycle begins again. I can usually look forward to a solid week or more of "good" Hellcat, where we can take in a movie or work out together. But lately that's become bittersweet for me too. This is always followed by a week or two where you can see the old patterns of addiction take hold. Now that I've mastered his cycle, in the back of my mind I'm always thinking of what's to come, and trying to figure out the best way to make it affect me and my life the least.

The upshot is that we have tentative plans to whip up a tasty brunch in the afternoon. I've offered to treat him to Christmas dinner at a restaurant of his choosing. Public Assistance doesn't provide him with a Christmas bonus. But this is all predicated on whether or not he can get up and get dressed. I may just be spending Christmas alone. Which I've done before, but for some reason, this alone feels really alone.

I'll probably try and treat it like any other day and ignore it best I can. The Ex is complaining of computer problems so maybe I'll clean up his system for him. A lot of places will be closed, but the diners will be open for food. Movie theaters do a decent business Christmas night. Maybe I'll troll the bars for a lost tourist to take home and unwrap.

I'm sorry this post is such a downer. I could have written a goopy post full of good cheer and love for all humanity. I have it in me. But that's not my reality right now. I wanted to write the truth, and I actually feel a bit better getting it all down "on paper". So, thanks for listening. And I do wish you all the happiest of holidays. If you find yourself lucky enough to be in the presence of good friends and loving family, take a moment to mark it, and thank the Universe for your good fortune. Fear not, we must endure the darkness to truly enjoy the light.

Heavy Is The Head That Wears The Crown

Is that a real quote? Or did I just lamely bastardize Shakespeare or something? But I have to address a problem at work. Funny thing is, I had a feeling this would happen, just not so soon.

Shortly after arriving at work and getting on the floor, I was approached by one of the waiters wanting to talk:

"What's up?"

"The Keymaster called me gay. I'm not a real gay rights, militant gay kind of guy..."

(interrupting) "Well I am. I need to know in what context he said it. Did he actually call you gay?"

In a nutshell, what happened was that The Keymaster, who has as horrible a case of verbal diarrhea as I've ever encountered, was lamenting to another employee the difficult time he's having controlling the staff. He explained further that today he was dealing with the waiter "Dave, who is gay, and you can't get anywhere with him." Unbeknownst to The Keymaster, the other employee he was addressing was also gay. So the other employee immediately approached Dave (not his real name) and let him know that the manager was not only talking about him, but telling other employees he was gay. Unfortunately, the result was that the next time Dave and The Keymaster interacted, The Keymaster also cursed at Dave. Since the pump was already primed, Dave took the opportunity to yell at The Keymaster that he should stop cursing at him and by the way, he knew he was telling people he was gay. Of course, this caused The Keymaster to go back to the other employee and express his dismay that Dave is upset that he talked about him being gay.

As I was talking to the other employee and trying to get the facts unvarnished, I elicited an unexpected confession. Apparently, The Keymaster was overheard walking through the club with a brand new employee just out of training. My name came up. It went something like:

"... And the other manager, Tom, who is gay, is easily excitable and over-reacts to things."

Now, if I have any non-gay readers (it could happen), I guess I should explain that referring to someone's sexuality as a descriptive term, as in gay Tom, is as offensive as Black Bob. Or maybe:

"Who has the scotch tape?"

"Mike."

"Mike?"

"Yeah, you know, Jewish Mike."

In other words, I'm going to have to bring basic sensitivity training to a grown man in New York City in 2004. I'm going to have to let him know that if he has a problem working with gay men that a) He ought to get out of the restaurant business, and b) he better learn to keep it to himself, as he's leaving himself and the club open to a lawsuit. I plan on asking for an apology. I am by no means in the closet or ashamed of my sexuality. However, discussing my sexuality with a newly hired employee is a) wildly unprofessional and b) a sign that you have issues on that subject.

In other words, I intend to bitch-slap The Keymaster and let him know he's just crossed the line with me. And while I'm trying always to be the bigger girl, I know where to find my inner nasty faggot. Don't make me go get her.

Coincidentally, an illustration as to why I need to make this point.

Is that a real quote? Or did I just lamely bastardize Shakespeare or something? But I have to address a problem at work. Funny thing is, I had a feeling this would happen, just not so soon.

Shortly after arriving at work and getting on the floor, I was approached by one of the waiters wanting to talk:

"What's up?"

"The Keymaster called me gay. I'm not a real gay rights, militant gay kind of guy..."

(interrupting) "Well I am. I need to know in what context he said it. Did he actually call you gay?"

In a nutshell, what happened was that The Keymaster, who has as horrible a case of verbal diarrhea as I've ever encountered, was lamenting to another employee the difficult time he's having controlling the staff. He explained further that today he was dealing with the waiter "Dave, who is gay, and you can't get anywhere with him." Unbeknownst to The Keymaster, the other employee he was addressing was also gay. So the other employee immediately approached Dave (not his real name) and let him know that the manager was not only talking about him, but telling other employees he was gay. Unfortunately, the result was that the next time Dave and The Keymaster interacted, The Keymaster also cursed at Dave. Since the pump was already primed, Dave took the opportunity to yell at The Keymaster that he should stop cursing at him and by the way, he knew he was telling people he was gay. Of course, this caused The Keymaster to go back to the other employee and express his dismay that Dave is upset that he talked about him being gay.

As I was talking to the other employee and trying to get the facts unvarnished, I elicited an unexpected confession. Apparently, The Keymaster was overheard walking through the club with a brand new employee just out of training. My name came up. It went something like:

"... And the other manager, Tom, who is gay, is easily excitable and over-reacts to things."

Now, if I have any non-gay readers (it could happen), I guess I should explain that referring to someone's sexuality as a descriptive term, as in gay Tom, is as offensive as Black Bob. Or maybe:

"Who has the scotch tape?"

"Mike."

"Mike?"

"Yeah, you know, Jewish Mike."

In other words, I'm going to have to bring basic sensitivity training to a grown man in New York City in 2004. I'm going to have to let him know that if he has a problem working with gay men that a) He ought to get out of the restaurant business, and b) he better learn to keep it to himself, as he's leaving himself and the club open to a lawsuit. I plan on asking for an apology. I am by no means in the closet or ashamed of my sexuality. However, discussing my sexuality with a newly hired employee is a) wildly unprofessional and b) a sign that you have issues on that subject.

In other words, I intend to bitch-slap The Keymaster and let him know he's just crossed the line with me. And while I'm trying always to be the bigger girl, I know where to find my inner nasty faggot. Don't make me go get her.

Coincidentally, an illustration as to why I need to make this point.

A Little Behind...

Sorry, I couldn't resist.

I accomplished quite a bit this week. Not the least of which is paying off my overdue rent. I've been behind by a month for about 6+ months. Between my shopping "problem" and the fact that I have a serious impulse control disorder, well, it adds up to my borrowing from Peter to pay Paul. And you'd think if I was paying Paul I'd be having more sex. In any case, being out of work for a couple of months didn't help. And is it a big surprise that my job managing a gay bar left me ineligible for unemployment? The pressure to get caught up weighs heavily on you week after week and then month after month. I had a recurring feeling of nagging desperation. Like no matter how much money I had or made, the wolves were at the door and it was all a house of cards ready to collapse.

Be that as it may, I've brazenly used/abused my being current on the rent to hit the landlord up for a new refrigerator. The old refrigerator is not working. Bottom line. The history of the old refrigerator dates back to the early 1990's. I'm not entirely sure when but it was sometime during the years with Beth. My first roommate. The refrigerator freezer had iced up and needed to be de-frosted. I was not the wizened (grizzled) Duchess I am today, but even then, I knew you let the freezer de-frost on its own. In fact, the freezer actually says so if you inspect it. At least this one did. Knowing that she was the impatient type, I passed this knowledge on to Beth. Alas, she decided to ignore me. This resulted in a late night work phone call with Beth sobbing that she had punctured the freezer with the knife she was chipping away the ice with, and all the gas inside had spewed into the kitchen. A repairman came in to patch the freezer and restore the freon but from that day forward, probably sometime in 1989 (!), it was never the same. The freezer was never cold enough and the refrigerator was OK... but things spoiled much faster than they should have. You couldn't keep ice cream for more than a couple of days. From late June to late August we had to buy daily bags of ice if we wanted cocktails. And we (I) wanted cocktails. I broached the subject of a new refrigerator several years ago with the landlord. At the time, the resulting increase in the monthly rent was off-putting. But my current roommates have convinced me that any rent increase will be easily offset by the cost of spoiled food and bags of ice.

So I've timed the request to coincide with renewing the lease in February. Sometime in January I expect to take delivery of a spankin' new refrigerator. In the meantime, I'll fantasize about what it would be like to eat the above man's ass for an hour or six.

Sorry, I couldn't resist.

I accomplished quite a bit this week. Not the least of which is paying off my overdue rent. I've been behind by a month for about 6+ months. Between my shopping "problem" and the fact that I have a serious impulse control disorder, well, it adds up to my borrowing from Peter to pay Paul. And you'd think if I was paying Paul I'd be having more sex. In any case, being out of work for a couple of months didn't help. And is it a big surprise that my job managing a gay bar left me ineligible for unemployment? The pressure to get caught up weighs heavily on you week after week and then month after month. I had a recurring feeling of nagging desperation. Like no matter how much money I had or made, the wolves were at the door and it was all a house of cards ready to collapse.

Be that as it may, I've brazenly used/abused my being current on the rent to hit the landlord up for a new refrigerator. The old refrigerator is not working. Bottom line. The history of the old refrigerator dates back to the early 1990's. I'm not entirely sure when but it was sometime during the years with Beth. My first roommate. The refrigerator freezer had iced up and needed to be de-frosted. I was not the wizened (grizzled) Duchess I am today, but even then, I knew you let the freezer de-frost on its own. In fact, the freezer actually says so if you inspect it. At least this one did. Knowing that she was the impatient type, I passed this knowledge on to Beth. Alas, she decided to ignore me. This resulted in a late night work phone call with Beth sobbing that she had punctured the freezer with the knife she was chipping away the ice with, and all the gas inside had spewed into the kitchen. A repairman came in to patch the freezer and restore the freon but from that day forward, probably sometime in 1989 (!), it was never the same. The freezer was never cold enough and the refrigerator was OK... but things spoiled much faster than they should have. You couldn't keep ice cream for more than a couple of days. From late June to late August we had to buy daily bags of ice if we wanted cocktails. And we (I) wanted cocktails. I broached the subject of a new refrigerator several years ago with the landlord. At the time, the resulting increase in the monthly rent was off-putting. But my current roommates have convinced me that any rent increase will be easily offset by the cost of spoiled food and bags of ice.

So I've timed the request to coincide with renewing the lease in February. Sometime in January I expect to take delivery of a spankin' new refrigerator. In the meantime, I'll fantasize about what it would be like to eat the above man's ass for an hour or six.

From My Mailbag.... Plus More Stuff

Hi Tom - Like the automatic subject line. Whenever I get to NYC.... Really writing about the testosterone therapy. My level was low so my Dr started me on the patch (seems to have no effect) and now the gel. Guess I'm wondering why you're taking it and what differences you have noticed. Don't know if I'm just placeboing or if there is a change. Thanks - D-----

Sent: Tuesday, December 14, 2004 3:52 AM

Hello D-----, How've you been? Well, I hope. Here's everything I know or was told by my Dr. re: testosterone replacement. Normally, men produce less testosterone naturally starting in their 40's. It's usually incremental and takes decades before the physical effects are dramatic. ( Meaning difficulty getting/maintaining an erection/difficulty achieving an orgasm/ lack of sex drive/ lack of energy.) In HIV+ men, a progressive and more rapid drop in testosterone production can be a simple side effect of the HIV and can occur anytime in your 20's/30's etc. I haven't found any information as to why this is, just that it is. Further, a drop in testosterone production can occur in otherwise healthy men although a drop for no reason is admittedly rarer.

Low testosterone levels are usually diagnosed from a few (or series) of blood tests that confirm a gradual downward trend in testosterone production. In my case, my levels fluctuated around the low/normal levels for the last eight months with the last two tests being consistently lower. So we decided on beginning treatment. I was given the option of receiving an injection followed by me giving myself injections of testosterone replacement. Aside from the obvious yikes! factor, I declined the option because my research showed that many health professionals think that flooding your system with that much testosterone at once is unhealthy. It taxes, among other things, the liver and other organs that are used to processing the body's testosterone output more gradually. It's why I chose the gel, which is absorbed through the skin over a six hour (approximately) period.

I've been on the therapy for about three weeks now and I have noticed some changes. The return of my morning erection has already been discussed and celebrated in my blog. And while it's not the piece of pipe I used to wake up to in my 20's, it's definitely a change. Further, I'm having a series of what I've dubbed IE's (inappropriate erections). Last week, I was headed to my favorite pizzeria for a couple of slices. A fantasy popped into my head as I was walking down the street and I found myself getting a raging, obvious hard-on in my cords. And, as usual, running commando, so I had to think of dead puppies and kittens and quick. Now, I really, really like the pizza there but honestly....

Today, I was doing cardio on a new piece of gym equipment and between my loose-fitting sweats and the boxer briefs I was wearing and the angle I was pumping my legs at..... dead puppies and kittens.

I have to say I'm noticing some personality changes as well but they're harder to prove. I'm irritable. But I'm always irritable so you'll just have to trust me when I say I'm more irritable than normal. I've had to stop myself on several occasions from exploding in public at a rude cashier or a stupid tourist. Fortunately, I was aware this would be a possibility and seem to be learning how to compensate.

The only way to tell for sure if the testosterone replacement is working is with a blood test. I'm assuming if you claim the patch was having no effect that you had a blood test confirming this. I'll be using the gel for another three weeks before I take a blood test to get some new numbers. Testosterone therapy is by no means experimental. It's a legitimate condition with a legitimate treatment. So I don't see how you would be given a placebo. Placebo's are usually given for drugs in an experimental phase. And while I'm no lawyer, I believe if you are involved in some sort of a program where you can possibly be given a placebo as a control group, you would have to sign some sort of document/agreement stating that. Unless your hometown is Tuskegee. My prescription comes from a national chain drugstore and goes by the brand name Androgel. I would think you could just Google up whatever you're taking and confirm it's the real deal.

I hope this is along the lines of what you were looking for. I admit, I was a bit apprehensive about (in effect) shutting off my balls. But in the end, I've never been a big ball man anyway. And if the trade off is the really (I hate to brag) enormous erection I popped yesterday when my masseur finished his "session" on me, and today when I took matters in hand myself, well then, god bless chemical enhancement.

Also-

Researchers at Rutgers develop three drugs they say destroy HIV.

I've been meaning to highlight his blog. Aside from being highly entertaining, he posted a link and then a very interesting essay on World AIDS day. This elicited a very thoughtful series of comments from a diverse group. All in all a wonderful job. I didn't comment because there was much to digest. There still is.

On a related tip, Larry Kramer sits down with Village Voice columnist Alisa Solomon and expounds on some thoughts and comments widely carried around the blogverse from his Nov. 7 Cooper Union speech. Make no mistake, I consider Larry Kramer to be a living gay hero. But I significantly disagreed with much of that speech. Here, with an interviewer forcing him to clarify and expand his line of thinking, I find his call to arms familiar and inspiring. I can only speak for myself, but I sense something's brewing in the land of cock smokers and muff divers. Be afraid, be very afraid. Read it here.

Hi Tom - Like the automatic subject line. Whenever I get to NYC.... Really writing about the testosterone therapy. My level was low so my Dr started me on the patch (seems to have no effect) and now the gel. Guess I'm wondering why you're taking it and what differences you have noticed. Don't know if I'm just placeboing or if there is a change. Thanks - D-----

Sent: Tuesday, December 14, 2004 3:52 AM

Hello D-----, How've you been? Well, I hope. Here's everything I know or was told by my Dr. re: testosterone replacement. Normally, men produce less testosterone naturally starting in their 40's. It's usually incremental and takes decades before the physical effects are dramatic. ( Meaning difficulty getting/maintaining an erection/difficulty achieving an orgasm/ lack of sex drive/ lack of energy.) In HIV+ men, a progressive and more rapid drop in testosterone production can be a simple side effect of the HIV and can occur anytime in your 20's/30's etc. I haven't found any information as to why this is, just that it is. Further, a drop in testosterone production can occur in otherwise healthy men although a drop for no reason is admittedly rarer.

Low testosterone levels are usually diagnosed from a few (or series) of blood tests that confirm a gradual downward trend in testosterone production. In my case, my levels fluctuated around the low/normal levels for the last eight months with the last two tests being consistently lower. So we decided on beginning treatment. I was given the option of receiving an injection followed by me giving myself injections of testosterone replacement. Aside from the obvious yikes! factor, I declined the option because my research showed that many health professionals think that flooding your system with that much testosterone at once is unhealthy. It taxes, among other things, the liver and other organs that are used to processing the body's testosterone output more gradually. It's why I chose the gel, which is absorbed through the skin over a six hour (approximately) period.

I've been on the therapy for about three weeks now and I have noticed some changes. The return of my morning erection has already been discussed and celebrated in my blog. And while it's not the piece of pipe I used to wake up to in my 20's, it's definitely a change. Further, I'm having a series of what I've dubbed IE's (inappropriate erections). Last week, I was headed to my favorite pizzeria for a couple of slices. A fantasy popped into my head as I was walking down the street and I found myself getting a raging, obvious hard-on in my cords. And, as usual, running commando, so I had to think of dead puppies and kittens and quick. Now, I really, really like the pizza there but honestly....

Today, I was doing cardio on a new piece of gym equipment and between my loose-fitting sweats and the boxer briefs I was wearing and the angle I was pumping my legs at..... dead puppies and kittens.

I have to say I'm noticing some personality changes as well but they're harder to prove. I'm irritable. But I'm always irritable so you'll just have to trust me when I say I'm more irritable than normal. I've had to stop myself on several occasions from exploding in public at a rude cashier or a stupid tourist. Fortunately, I was aware this would be a possibility and seem to be learning how to compensate.

The only way to tell for sure if the testosterone replacement is working is with a blood test. I'm assuming if you claim the patch was having no effect that you had a blood test confirming this. I'll be using the gel for another three weeks before I take a blood test to get some new numbers. Testosterone therapy is by no means experimental. It's a legitimate condition with a legitimate treatment. So I don't see how you would be given a placebo. Placebo's are usually given for drugs in an experimental phase. And while I'm no lawyer, I believe if you are involved in some sort of a program where you can possibly be given a placebo as a control group, you would have to sign some sort of document/agreement stating that. Unless your hometown is Tuskegee. My prescription comes from a national chain drugstore and goes by the brand name Androgel. I would think you could just Google up whatever you're taking and confirm it's the real deal.

I hope this is along the lines of what you were looking for. I admit, I was a bit apprehensive about (in effect) shutting off my balls. But in the end, I've never been a big ball man anyway. And if the trade off is the really (I hate to brag) enormous erection I popped yesterday when my masseur finished his "session" on me, and today when I took matters in hand myself, well then, god bless chemical enhancement.

Also-

Researchers at Rutgers develop three drugs they say destroy HIV.

I've been meaning to highlight his blog. Aside from being highly entertaining, he posted a link and then a very interesting essay on World AIDS day. This elicited a very thoughtful series of comments from a diverse group. All in all a wonderful job. I didn't comment because there was much to digest. There still is.

On a related tip, Larry Kramer sits down with Village Voice columnist Alisa Solomon and expounds on some thoughts and comments widely carried around the blogverse from his Nov. 7 Cooper Union speech. Make no mistake, I consider Larry Kramer to be a living gay hero. But I significantly disagreed with much of that speech. Here, with an interviewer forcing him to clarify and expand his line of thinking, I find his call to arms familiar and inspiring. I can only speak for myself, but I sense something's brewing in the land of cock smokers and muff divers. Be afraid, be very afraid. Read it here.

Perspective

An easy night on the job. I actually had some fun. I had enough other competent management with me that I could take the time to joke around with the staff, enjoy some time at the concert and still be home by 1:15. The Hellcat was still up, so we had a lovely chat before bed.

Work is ....Interesting. It's very heterosexual. The world is. I'm just not used to that. There's only two overtly gay men working there besides me. The only open lesbian was just fired. I've gotten some signals that we have a couple of bi girls on staff, and I had a security guy tell me that one of the male performers was so pretty "I'd do him". I didn't react. There's very little anti-gay sentiment from people. Racism is far more prevalent. I haven't actually said the words "I'm gay" to anyone connected with work. On the one hand, I don't operate under the delusion that I'm able to pass, that I'm a "masculine" male. First of all, I don't give a fuck. The concept of "masculinity" to me is fucking stupid. I'm a guy. I like my guy parts. I have no desire to be a woman. "The Duchess" is a gay male persona. It's fun and funny. But I also feel no need to "play" a guy or live up to some masculine ideal. I'm a gay man. How "butch" can you be getting royally dicked?

So I assume they know I'm gay. But I'm giving way too much credit to some heterosexuals. Because they're more stupid than you would think. Some of them are so completely unaware of the other people in their environment that the fact that I'm gay would be stunning. I don't care. I've told stories about The Hellcat. I've talked about The Ex. I haven't characterized The Ex as the real Ex, however. I'll get around to it. One of the things I like about the new job is the fact that it's such a big place, that a level of impersonal is built right in. I had 18 servers scheduled tonight. I can stick and run. Jump in and take care of a problem, tell a joke. I can be fabulous for a second and then take off. I'm not hiding, I'm being superficial. Superficial suits me right now.

The funny thing is, I've had more than one employee or manager comment about how "laid-back" or "cool" I am. How nothing seems to bother me. Of course, that's just not true. What is true is that I have a rich and full (for better or worse) life outside of work. I'm HIV+, I live with my ex-lover, my other room mate is a meth addict, I've got a serious shopping problem, I'm currently trying to resolve whether my responses are the result of testosterone therapy or I'm an extremely and inappropriately angry individual. In spite of it all, the upshot is that I like to do a good job, it's important that my staff does a good job, but in the grand scheme of things, it's a nightclub. It's food. We do the best we can. My job does not define who I am. Too many other things are more important. So I take on a "Buddha" quality because while I don't have all the secrets, I have a couple. And one of them is to relax, you're smart enough. It'll all get done.

An easy night on the job. I actually had some fun. I had enough other competent management with me that I could take the time to joke around with the staff, enjoy some time at the concert and still be home by 1:15. The Hellcat was still up, so we had a lovely chat before bed.

Work is ....Interesting. It's very heterosexual. The world is. I'm just not used to that. There's only two overtly gay men working there besides me. The only open lesbian was just fired. I've gotten some signals that we have a couple of bi girls on staff, and I had a security guy tell me that one of the male performers was so pretty "I'd do him". I didn't react. There's very little anti-gay sentiment from people. Racism is far more prevalent. I haven't actually said the words "I'm gay" to anyone connected with work. On the one hand, I don't operate under the delusion that I'm able to pass, that I'm a "masculine" male. First of all, I don't give a fuck. The concept of "masculinity" to me is fucking stupid. I'm a guy. I like my guy parts. I have no desire to be a woman. "The Duchess" is a gay male persona. It's fun and funny. But I also feel no need to "play" a guy or live up to some masculine ideal. I'm a gay man. How "butch" can you be getting royally dicked?

So I assume they know I'm gay. But I'm giving way too much credit to some heterosexuals. Because they're more stupid than you would think. Some of them are so completely unaware of the other people in their environment that the fact that I'm gay would be stunning. I don't care. I've told stories about The Hellcat. I've talked about The Ex. I haven't characterized The Ex as the real Ex, however. I'll get around to it. One of the things I like about the new job is the fact that it's such a big place, that a level of impersonal is built right in. I had 18 servers scheduled tonight. I can stick and run. Jump in and take care of a problem, tell a joke. I can be fabulous for a second and then take off. I'm not hiding, I'm being superficial. Superficial suits me right now.

The funny thing is, I've had more than one employee or manager comment about how "laid-back" or "cool" I am. How nothing seems to bother me. Of course, that's just not true. What is true is that I have a rich and full (for better or worse) life outside of work. I'm HIV+, I live with my ex-lover, my other room mate is a meth addict, I've got a serious shopping problem, I'm currently trying to resolve whether my responses are the result of testosterone therapy or I'm an extremely and inappropriately angry individual. In spite of it all, the upshot is that I like to do a good job, it's important that my staff does a good job, but in the grand scheme of things, it's a nightclub. It's food. We do the best we can. My job does not define who I am. Too many other things are more important. So I take on a "Buddha" quality because while I don't have all the secrets, I have a couple. And one of them is to relax, you're smart enough. It'll all get done.

Here's Some Stuff ...

POZ Magazine has an interesting article about igniting fresh debate regarding HIV undetectability and long-term health. -via TheBody.com

Texas lawman needs some schoolin'.

Gay Republican (!) Mayor Re-Elected.

Mormon parents wait 'till their son dies to support him.

Ellen! Stop discussing your realtionships in print!

POZ Magazine has an interesting article about igniting fresh debate regarding HIV undetectability and long-term health. -via TheBody.com

Texas lawman needs some schoolin'.

Gay Republican (!) Mayor Re-Elected.

Mormon parents wait 'till their son dies to support him.

Ellen! Stop discussing your realtionships in print!

Now That's An Office Party

Eight closing shifts in a row. And tonight was quite the cap on the week-plus. Not in a bad way. More in a typical New York City way. We hosted the Mother of all Holiday parties. It was an intimate affair for a meager 800 people. They rented the entire club for the entire night. That ain't cheap, folks. Of course, when you own/run this set of properties, I guess you can afford to drop a few dollars.

Besides, in an effort to not be (I assume) totally vulgar in a display of wealth, this particular company uses their annual holiday party to raise money for charity. Specifically, a foundation to research/cure pancreatic cancer. Trust me, it's not as much of a buzzkill as you would think. You can, in fact, get loaded and pack on those holiday pounds while raising money for cancer research. I overheard a relatively reliable source quote a total raised as 1 million dollars.

Logistically, the majority of the planning was done by a squadron of party planners. Curiously, they all wore identical black pantsuits. They frightened me a bit. In addition, we had about 30+ of our own staff available and plenty of managers. That would be me. I pointed a lot. I listened intently to my walkie talkie at conversations that had nothing to do with me. I snacked on "horse ovaries". In short, I was superfluous. And I got a small cash bonus from the client for my ( mediocre) attention. It beats a sharp stick in the eye.

You know that you're at a party that's spent some money when Chris Rock introduces the house band. You know you're at a party that's spent some money when they've paid for a 5 hour open premium bar for 875 people. And I guess when you own Radio City Music Hall, and all that's attached to the property, it should come as no surprise that instead of some kareoke set-up, where drunken office staffers warble to Britney Spears tracks from four years ago, you enjoy a performance from The Radio City Music Hall Rockettes. I confess, in the end, The Duchess could not resist being in such close photographic proximity to The Rockettes. Let's just say that assuming I have the time this weekend, my Christmas card this year will be truly memorable.

Eight closing shifts in a row. And tonight was quite the cap on the week-plus. Not in a bad way. More in a typical New York City way. We hosted the Mother of all Holiday parties. It was an intimate affair for a meager 800 people. They rented the entire club for the entire night. That ain't cheap, folks. Of course, when you own/run this set of properties, I guess you can afford to drop a few dollars.

Besides, in an effort to not be (I assume) totally vulgar in a display of wealth, this particular company uses their annual holiday party to raise money for charity. Specifically, a foundation to research/cure pancreatic cancer. Trust me, it's not as much of a buzzkill as you would think. You can, in fact, get loaded and pack on those holiday pounds while raising money for cancer research. I overheard a relatively reliable source quote a total raised as 1 million dollars.

Logistically, the majority of the planning was done by a squadron of party planners. Curiously, they all wore identical black pantsuits. They frightened me a bit. In addition, we had about 30+ of our own staff available and plenty of managers. That would be me. I pointed a lot. I listened intently to my walkie talkie at conversations that had nothing to do with me. I snacked on "horse ovaries". In short, I was superfluous. And I got a small cash bonus from the client for my ( mediocre) attention. It beats a sharp stick in the eye.

You know that you're at a party that's spent some money when Chris Rock introduces the house band. You know you're at a party that's spent some money when they've paid for a 5 hour open premium bar for 875 people. And I guess when you own Radio City Music Hall, and all that's attached to the property, it should come as no surprise that instead of some kareoke set-up, where drunken office staffers warble to Britney Spears tracks from four years ago, you enjoy a performance from The Radio City Music Hall Rockettes. I confess, in the end, The Duchess could not resist being in such close photographic proximity to The Rockettes. Let's just say that assuming I have the time this weekend, my Christmas card this year will be truly memorable.

Awww, He's Sick.

The Ex came home from work early this afternoon. He was sick. It seemed to be a stomach flu. From the way he was whining and moaning, you would think he was the first person ever stricken with it. He did throw up. I assume his stomach was cramping. But honestly, if you didn't know better you would think his death was imminent. He went from his bedroom to the bathroom to the couch and around again. He balled up in the dark on his bed, and then sat and shivered on the couch. He drew a hot bath. Then he started the whole circuit over again. He threw his forearm across his eyes and moaned. He laid in bed and groaned over and over. There seemed to be no end to his suffering. Well, actually the end came when I left. I'm sorry, I couldn't stand it. It was just soooooo pathetic. I had to go to work anyway and I bailed a half hour early. Yes, I realize I was just ill myself and I was, of course, feeling sympathy. But my god, the way he was carrying on....

Besides, I have a little resentment in the bank. When I was sick The Ex was out of town and of no help. The Hellcat responded to my informing him I was sick to going out and getting high and leaving me to care for his dog. I was new at the job at the time. Every time I mentioned I was sick I was ignored or the subject was changed. I spoke to my boss after the fact.

"You didn't seem sick at all."

Apparently, I needed to curl into a ball and moan and groan as if I was about to breathe my last. Stupid me for trying to soldier through it. But I felt like absolute hell and nobody (except my Mom and Dad via phone) lifted a finger to help or comfort me. So unfortunately I have no well of sympathy to draw on to try and tend to The Ex. She's on her own.

P.S. (Without naming names) Do you not have a creative thought in your sweaty hairy fat head? You've stolen my header, my template and the quotes at the top of my blog. Get a fucking life and do something original, loser.

The Ex came home from work early this afternoon. He was sick. It seemed to be a stomach flu. From the way he was whining and moaning, you would think he was the first person ever stricken with it. He did throw up. I assume his stomach was cramping. But honestly, if you didn't know better you would think his death was imminent. He went from his bedroom to the bathroom to the couch and around again. He balled up in the dark on his bed, and then sat and shivered on the couch. He drew a hot bath. Then he started the whole circuit over again. He threw his forearm across his eyes and moaned. He laid in bed and groaned over and over. There seemed to be no end to his suffering. Well, actually the end came when I left. I'm sorry, I couldn't stand it. It was just soooooo pathetic. I had to go to work anyway and I bailed a half hour early. Yes, I realize I was just ill myself and I was, of course, feeling sympathy. But my god, the way he was carrying on....

Besides, I have a little resentment in the bank. When I was sick The Ex was out of town and of no help. The Hellcat responded to my informing him I was sick to going out and getting high and leaving me to care for his dog. I was new at the job at the time. Every time I mentioned I was sick I was ignored or the subject was changed. I spoke to my boss after the fact.

"You didn't seem sick at all."

Apparently, I needed to curl into a ball and moan and groan as if I was about to breathe my last. Stupid me for trying to soldier through it. But I felt like absolute hell and nobody (except my Mom and Dad via phone) lifted a finger to help or comfort me. So unfortunately I have no well of sympathy to draw on to try and tend to The Ex. She's on her own.

P.S. (Without naming names) Do you not have a creative thought in your sweaty hairy fat head? You've stolen my header, my template and the quotes at the top of my blog. Get a fucking life and do something original, loser.

Cold and Wet, Tired You Bet

Could this weather suck a little more? And right smack dab in the dead of winter. It was dark and cold and rainy here in New York today. My mood was colored by the weather all day. Dark and cold. I didn’t want to be at work before I ever got there. Plus I’ve closed the bar every night since Wednesday and my next day off isn’t until Friday. Eight closing shifts in a row suck. I’ve overused suck. My room is a bit on the nippy side from my drafty windows. How cute do I look in my black sweats and Buffalo Bills football sweatshirt? Very cute indeed. Enough complaining, I promised a story.

Flashback…..

About a month ago. I’m at the gym and my workout is done. I head for the showers and I freely admit I hit the steam room to check out the cruising action. Honestly though (and this was before the testosterone made me a horn dog) I wasn’t really looking looking. Not finding anything remotely interesting, I returned to the showers. My intent was to shower up, do some grocery shopping and head home. Coincidentally (I SWEAR), the shower I chose afforded me a view of the sauna through the partly opened curtain. I say partly open because while I always pull the curtain, I don’t insure that it’s not possible to see a millimeter of my skin when I’m showering. I pull the curtain. If you can see my ass you see my ass. If I’ve got any part showing any other guy doesn’t have, feel free to point and scream.

So at some point I looked up while showering and was able to see through the sauna door. I spotted a nice looking boy. He looked to be in his early twenty’s. He was looking directly at me. I was startled at first and then slightly turned on. It was only then I realized there was someone else in the sauna. He was a bit older, maybe thirty and blond and slim. He was looking at me too. The exhibitionist and the voyeur in me were now fully alert. I continued showering and soaping various parts. I freely admit I unabashedly soaped up my naughty pieces and paid them extra attention.

It was only during my shower show that I noticed something. The twenty something boy (and he was more boy than man) was leaning forward. Dramatically forward. Bent at the waist forward. It was then I noticed the older blond guy’s arm. It was behind the other boy. Am I seeing what I think I’m seeing? And they’re both still staring at me. Of course, I can’t resist the invitation or the speculation.

I turn off my shower and head for the sauna. Modesty and safety seem to take over as they both act as if nothing is happening. I let them know it’s cool with a quick crotch massage (on myself), at which point they both drop towels to reveal hard-on’s. Now that I’m closer, I get a chance to see them both. The twenty something boy is slim with a few tattoos. He’s got a cute treasure trail to his cock but no chest hair to speak of. He looks to be about 5’8” and 140. In spite of that he’s got a nice 7” inch cock that’s pretty thick. He's scruffy. I love scruffy. The older blond is also about 5’8” and slim. He’s got a bit of chest hair but not an ounce of body fat and about a 6” cock that’s bone-hard. Once they’ve confirmed they’ve hooked me in they resume their show. The dark haired East Village tattooed boy leans forward. At which point the blond runs a hand down his back and starts fingering his hole. Damn! After a couple of minutes the blond sticks a finger in his mouth to spit-slick it and slowly jams it up the boy’s hole. The East Village boy moans. I’m bone-hard. The blond guy is alternately jerking off and watching me play with my package. By now I’m leaking pre-cum and I squeeze a bit on to my finger and eat it. The East Village boy likes it and I get another moan. One finger becomes two.

“That’s fuckin hot.”

“It feels good.”

“Fuck yourself on his fingers, man.”

“You like it?”

“Fuck yeah.”

Two fingers become three and now the East Village boy is really riding the blond man’s hand. I’m totally turned on and amazed that he’s riding the blonde’s hand like a fucking pony. Eventually, the East Village boy is completely turned on and moaning like a bitch as I jerk my cock and wait for him to cross the line. Inappropriate public behavior? You bet. But part of the turn-on, obviously, was that they wanted to put on a show for somebody. The other part was that it was in public in the middle of the day. I was only too happy to be entertained. The East Village boy shot a nice load, at which point I responded by blowing a hot load on his chest. That brought the blond guy off too.

"That was fucking hot."

"Yeah man, thanks."

I've seen the blond again several times, but I've never again seen the scruffy East Village boy who got finger fucked at the gym.

Could this weather suck a little more? And right smack dab in the dead of winter. It was dark and cold and rainy here in New York today. My mood was colored by the weather all day. Dark and cold. I didn’t want to be at work before I ever got there. Plus I’ve closed the bar every night since Wednesday and my next day off isn’t until Friday. Eight closing shifts in a row suck. I’ve overused suck. My room is a bit on the nippy side from my drafty windows. How cute do I look in my black sweats and Buffalo Bills football sweatshirt? Very cute indeed. Enough complaining, I promised a story.

Flashback…..

About a month ago. I’m at the gym and my workout is done. I head for the showers and I freely admit I hit the steam room to check out the cruising action. Honestly though (and this was before the testosterone made me a horn dog) I wasn’t really looking looking. Not finding anything remotely interesting, I returned to the showers. My intent was to shower up, do some grocery shopping and head home. Coincidentally (I SWEAR), the shower I chose afforded me a view of the sauna through the partly opened curtain. I say partly open because while I always pull the curtain, I don’t insure that it’s not possible to see a millimeter of my skin when I’m showering. I pull the curtain. If you can see my ass you see my ass. If I’ve got any part showing any other guy doesn’t have, feel free to point and scream.

So at some point I looked up while showering and was able to see through the sauna door. I spotted a nice looking boy. He looked to be in his early twenty’s. He was looking directly at me. I was startled at first and then slightly turned on. It was only then I realized there was someone else in the sauna. He was a bit older, maybe thirty and blond and slim. He was looking at me too. The exhibitionist and the voyeur in me were now fully alert. I continued showering and soaping various parts. I freely admit I unabashedly soaped up my naughty pieces and paid them extra attention.

It was only during my shower show that I noticed something. The twenty something boy (and he was more boy than man) was leaning forward. Dramatically forward. Bent at the waist forward. It was then I noticed the older blond guy’s arm. It was behind the other boy. Am I seeing what I think I’m seeing? And they’re both still staring at me. Of course, I can’t resist the invitation or the speculation.

I turn off my shower and head for the sauna. Modesty and safety seem to take over as they both act as if nothing is happening. I let them know it’s cool with a quick crotch massage (on myself), at which point they both drop towels to reveal hard-on’s. Now that I’m closer, I get a chance to see them both. The twenty something boy is slim with a few tattoos. He’s got a cute treasure trail to his cock but no chest hair to speak of. He looks to be about 5’8” and 140. In spite of that he’s got a nice 7” inch cock that’s pretty thick. He's scruffy. I love scruffy. The older blond is also about 5’8” and slim. He’s got a bit of chest hair but not an ounce of body fat and about a 6” cock that’s bone-hard. Once they’ve confirmed they’ve hooked me in they resume their show. The dark haired East Village tattooed boy leans forward. At which point the blond runs a hand down his back and starts fingering his hole. Damn! After a couple of minutes the blond sticks a finger in his mouth to spit-slick it and slowly jams it up the boy’s hole. The East Village boy moans. I’m bone-hard. The blond guy is alternately jerking off and watching me play with my package. By now I’m leaking pre-cum and I squeeze a bit on to my finger and eat it. The East Village boy likes it and I get another moan. One finger becomes two.

“That’s fuckin hot.”

“It feels good.”

“Fuck yourself on his fingers, man.”

“You like it?”

“Fuck yeah.”

Two fingers become three and now the East Village boy is really riding the blond man’s hand. I’m totally turned on and amazed that he’s riding the blonde’s hand like a fucking pony. Eventually, the East Village boy is completely turned on and moaning like a bitch as I jerk my cock and wait for him to cross the line. Inappropriate public behavior? You bet. But part of the turn-on, obviously, was that they wanted to put on a show for somebody. The other part was that it was in public in the middle of the day. I was only too happy to be entertained. The East Village boy shot a nice load, at which point I responded by blowing a hot load on his chest. That brought the blond guy off too.

"That was fucking hot."

"Yeah man, thanks."

I've seen the blond again several times, but I've never again seen the scruffy East Village boy who got finger fucked at the gym.

It's Late

Worked tonight and Air Supply did two shows. They were wonderful and sold out both shows. The crowds were great and the shows were very entertaining. Air Supply. I'm showing my age.

Worked tonight and Air Supply did two shows. They were wonderful and sold out both shows. The crowds were great and the shows were very entertaining. Air Supply. I'm showing my age.

I'm Sorry, I Know I Promised You A Whole 'Nother Story. I Forgot It Was AIDS' Birthday.

Resources:

The Body.com- HIV/AIDS 411

Gay Men's Health Crisis

Body Positive

The Hive - Social/support group for HIV+

Mind/Body Medical Institute

Seattle Treatment Education Project- STEP EZine

Callen-Lorde Community Health Center- HIV/AIDS medical care in NYC. They take good care of me.

The Center- LGB&T Community Center

The Starfish Project- collecting unused AIDS drugs for worldwide patients who can't afford them

Meanwhile ... worldwide:

November 28, 2004 A HOLLOWED GENERATION PLUNGE IN LIFE EXPECTANCY

Hut by Hut, AIDS Steals Life in a Southern Africa Town By MICHAEL WINES and SHARON LaFRANIERE

copyright 2004. The New York Times.com

AVUMISA, Swaziland - Victim by victim, AIDS is steadily boring through the heart of this small town. It killed the mayor's daughter. It has killed a fifth of the 60 employees of the town's biggest businessman. It has claimed an estimated one in eight teachers, several health workers and 2 of 10 counselors who teach prostitutes about protected sex. One of the 13 municipal workers has died of AIDS. Another is about to. A third is H.I.V.-positive.

By one hut-to-hut survey in 2003, one in four households on the town's poorer side lost someone to AIDS in the preceding year. One in three had a visibly ill member.

That is just the dead and the dying. There is also the world they leave behind. AIDS has turned one in 10 Lavumisans into an orphan. It has spawned street children, prostitutes and dropouts. It has thrust grandparents and sisters and aunts into the unwanted roles of substitutes for dead fathers and mothers. It has bred destitution, hunger and desperation among the living.

It has the appearance of a biblical cataclysm, a thousand-year flood of misery and death. In fact, it is all too ordinary. Tiny Lavumisa, population 2,000, is the template for a demographic plunge taking place in every corner of southern Africa.

Across the region, AIDS has reduced life expectancy to levels not seen since the 1800's. In six sub-Saharan nations, the United Nations estimates, the average child born today will not live to 40.

Here in Swaziland, a kingdom about the size of New Jersey with one million people tucked into South Africa's northeast corner, two in five adults are infected with H.I.V., the virus that causes AIDS. Life expectancy now averages 34.4 years, the fourth lowest on earth. Fifteen years ago, it stood at 55. By 2010, experts predict, it will be 30.

Epidemics typically single out the aged and young - the weak, not those at society's core. So what happens to a society when its fulcrum - its mothers and fathers, teachers, nurses, farm workers, bookkeepers, cooks, clerks - die in their prime?

Part of the answer lies in Lavumisa, where two visitors spent five weeks recently talking to more than 60 residents, following the terrible ripples that an unrestrained epidemic is sending through the community. Sickness leads to death, death leads to destitution, destitution worsens a host of social ills, from illiteracy to prostitution to abandoned babies. Multiply a single illness or death scores of times, and a town like Lavumisa begins to unravel.

The average life expectancy here is 34 years, but there are fewer and fewer 34-year-olds - just the very young and the old, struggling to do a 34-year-old's job.

Today, Lavumisa's schools are collapsing. Crime is climbing. Medical clinics are jammed. Family assets are sold to fend off hunger. The sick are dying, sometimes alone, because they are too many, and the caretakers are too few.

Much of this is occurring because adults whose labors once fed children and paid school fees and sustained families are dead. Lavumisa's lost generation of adults has reached beyond the grave, robbing survivors of their aspirations, reducing promising lives to struggles for existence.

Sixteen-year-old Nkuthula Madlopha wanted to be a police officer. Instead, next year she will till her grandparents' fields, filling in for her dead parents. Her brother will herd livestock.

Their grandmother, Vayillina Madlopha, wanted a quiet old age. Instead, at 80, she is a new mother. "I thought my daughters-in-law would be serving me food, washing for me and cleaning the yard," she said. "Now I must start afresh."

Eleven-year-old Ntokozo wanted to be a third grader. Instead, he lies on the floor of his one-room hut, his knees swollen like baseballs and his mouth pitted with sores. His mother, who died in May, infected him with H.I.V., either during her pregnancy or later as he helped tend her oozing sores. His sister, Nkululeko Masimula, 26, wanted a job. " I wanted to have my own business; to be a hairdresser or a wholesaler," she said. Instead, she tends her brother and their 61-year-old grandmother. She sells the family's chickens to raise money for food. Finding the $20 a month required to take her brother to the nearest antiretroviral drug site, 60 miles away, is a pipe dream.

Dido Khosa, 9, wants his mother back. "She used to cook food, wash my clothes, do things for me," he said, sobbing. Instead, he describes a life of regular beatings by his father and his father's girlfriend and periodic escapes to the homes of neighbors.

Delisile Nyandeli, slim and pretty, wanted her own home and family. Instead, she cares not only for her orphaned sisters and brothers, but also for the orphaned children of two sisters who died of AIDS and whose husbands fled. At age 20, she is a mother to nine other children besides her own boy.

"Today, when I was cleaning this house," she said, "I thought about it - if my mother were alive, she would be the one doing this. Because when my sisters don't have any pencils or other things they need for school, they come to me.

"And I can't help them."

A Hard Life Made Harder

Baked by drought, blessed with a single paved street, a gas station, two liquor stores, two bars and a wretched crafts stand for tourists speeding from the adjacent South Africa border post, Lavumisa clings to Swaziland's lower rungs. Life would be hard here, even without AIDS.

A mostly rainless decade has discouraged most farmers from planting maize, the staple crop, much less the cotton that once underpinned the local economy. Many survive on homegrown chickens and pigs, donations from the World Food Program and the kindness of relatives who work across the border or in Swaziland's better-off cities.

The town does not keep death statistics. Most people quietly bury relatives in their yards or nearby fields rather than buy a cemetery plot. But Mzweleni Dlamini, the acting chief for Lavumisa and the surrounding region, does not need a tally to tell him the toll is very high.

Two years ago, he shifted his regular meeting with subordinates from weekends to Tuesdays because Saturdays and Sundays were consumed by funerals. Now he has given permission for weekday funerals because there are too many dead for the traditional weekend services alone.

With the dead gone, it is the impoverished survivors' turn to suffer.

At Lavumisa Primary School, a beige L-shaped building of concrete classrooms clumped around a red dirt yard, enrollment has fallen nearly 9 percent in five years, to 494 students, as children drop out to support families. One in three students has lost at least one parent.

Nomfundo, a 15-year-old seventh grader, made the four-mile trek home from school one recent day with her brother, Ndabendele, 10. He carried his books in a torn plastic bag. She sported the shaved head customary for girls in mourning.

Their 34-year-old mother, a domestic worker, died Aug. 29; their father died in 2003. Care of the children has fallen to their grandmother, Esther Simelane, 53, who has been jobless for 14 years.

Since the illnesses began, she has sold four of the family's eight goats to raise money for food.

"Wheesh! Now I can feel the hardship," Nomfundo said. "Who is going to pay my school fees? Even the clothes. Where am I going to get them?" She tugged at her school uniform skirt, riddled with holes and hemmed several times to hide tears.

"I feel small," she said. "We used to have track suits. Now we no longer have track suits. Other kids say, 'Oh, now you don't have a track suit. Not even shoes! Now you are on the same level as us.' "

Actually, the two children are headed lower. Unbeknownst to them, their grandmother has tested positive for H.I.V., apparently contracting the virus while dressing her daughter's bleeding sores. Mrs. Simelane has kept the news from Nomfundo and her brother to spare them further trauma.

Should Nomfundo manage to stay in school another year, she will move up to Ndabazezwe High School. Elphas Z. Shiba, the headmaster, keeps careful track of his 366 students in stacks of ledgers.

Mr. Shiba can state that at the beginning of this year, Ndabazezwe High had 40 students who had lost at least one parent. Nine months later, there were 73, 20 of whom had lost both father and mother, nearly all of whom are desperately poor. A decade ago, Mr. Shiba said, the school had perhaps five orphans, none of them needy.

Both the primary and the high school are staggering under the burden of feeding and educating a growing army of orphans who, by and large, cannot pay the school fees. The state has pledged to pay to educate orphans, but so far it has picked up but half the Lavumisa primary-school fees. Mr. Shiba said the high school was getting a mere $15 of the $100 a year it costs to educate each orphan.

Ndabazezwe High School is now deeply in debt by Swazi standards. It owes $275 for electricity; $200 for water; $260 for books and hundreds more for office equipment. The security guards have not been paid in two months. Borrowed money bought the woodworking and home-economics materials needed for final exams. Even school lunches are hit-or-miss.

Mr. Shiba and Stephen Nxumalo, the headmaster at Lavumisa Primary, reluctantly intend to carry out a resolution adopted in May by the nation's main teachers' organization. Starting in January, students who do not pay their fees - currently about 100 in the primary school, 258 in the high school - will be barred from classes.

"The number of those who don't pay keeps increasing," Mr. Nxumalo said. "It's because of the orphans. We are going to send them home, because we have no option."

Tibuthye, Sandile and Nkuthula Madlopha stand to be among the first to go.

Their parents are buried on a hillside outside Lavumisa. Their father died in 1999 at 46; their mother three years later at 32. The father's parents, 80-year-old Vayillina Madlopha and her 82-year-old husband, Ellias, now raise three children, ages 10, 12 and 16, on Ellias's $75-a-month pension.

For the old couple, the son's death was a double blow. Gone is the $30 a month that he gave them to supplement their meager income. Gone is the extra labor and money for diesel fuel that he provided during the planting season on their farm. Their fields of maize, pumpkin and beans now lie fallow.

After school one day, Mrs. Madlopha bent over an open fire, teaching 10-year-old Tibuthye how to bake buns to sell at school for a few cents. "I am old, I will die," she said. "They must learn how to work, so they will be able to do these things on their own."

Nkuthula, 16, has plans for after her graduation. "I want to be a police," she said in halting English. But the Madlophas cannot afford to fix their broken tractor, much less to educate three children.

"They need too many exercise books and school uniforms," Mrs. Madlopha said. "We can't afford all that. We are failing them."

Grim Choices for Children

What has befallen the Madlophas is happening across Lavumisa. When a family loses a parent to AIDS, public health experts here say, the household production of maize quickly falls by half; the number of livestock owned by nearly a third. It is the equivalent of draining the bank account.

Unable to both feed and educate their children, impoverished single parents frequently farm them out to relatives, following an axiom of Swazi culture that one takes care of one's own blood, no matter the cost. One in six families has already has taken in a child left parentless by AIDS, according to the World Food Program.

"We Swazis don't believe there are orphans," said Lavumisa's mayor, Victor Simelane, who is not related to Esther. "But now the extended families cannot support the magnitude of the orphans."

Increasingly, such children face a grim choice: either seek shelter with whomever will take them in, or live on the streets.

As he walked down Lavumisa's main drag, yards from the South African border gate one afternoon last month, the mayor spotted Thabiso Mavimbela, 12, darting across the macadam. "You see," he said, "here is one of these street kids. They don't have extended families. They're loitering around the town." Five years ago, he said, such kids did not exist.

Thabiso's world is a fearful place. He spends much of his after-school time on Lavumisa's streets. After his mother died five years ago, his father abandoned him. He ended up in his great-grandmother's mud-and-stone hut, , its walls a checkerboard of holes and openings stuffed with rags, down a rutted dirt road from the primary school.

The two sleep on grass mats on the dirt floor. Thabiso's uncle occupies the only foam mattress. Thabiso has no toothbrush, no washcloth, nothing except his tattered clothes. At night, he said, mice bite his feet.

Those are the least of his problems. "My uncle tells me: 'When your great-grandmother dies, I will kill you too,' " he said. Panicky, he grinds his wet eyes into the cuff of his green-and-yellow school uniform. "I know that when she dies, I have to be killed. I don't have any other place to go."

Thabiso's uncle says the boy is treated well. But in an interview in early September, his aunt, Thembi Simelane, said Thabiso sometimes sought refuge in her home, declaring that he would rather sleep on his mother's grave than in a hut with his uncle.

Ms. Simelane once was Thabiso's lifeline. Despite losing her husband to AIDS three years ago and rearing her own five children, she supported the child with profits from clothes bought in South Africa and resold in Lavumisa. But she had to abandon that work last year when she, too, fell ill.

Last January, she tested positive for H.I.V. "My days are numbered," she told a visitor in September.

She showed a speechless Thobile Jele, a social worker at the mayor's office, a will scrawled in black crayon on school notebook paper. It bequeathed to Ms. Jele her five children. It did not mention Thabiso.

At the end of October, Ms. Simelane died.

Roaming Lavumisa's streets with Thabiso is Dido Khosa, 9, whose mother died in 2002 at age 28. His father and his new girlfriend now care for him, after a fashion.

When a neighbor questioned him some weeks ago, Dido told her he had spent two days alone at home without food.

Filching family money to buy bread, he said, brings a stiff penalty. Pulling down his dirty sweat pants, Dido displayed a two-inch scar on his thigh where, he said, his father had beaten him with a pipe. He worried an abscessed tooth with a stick.

"I eat when there is food at school," he said.

Asked who takes care of him, he replied, "No one."

In August, Lavumisans noted a new sign of the growing stress on families: two abandoned babies, left on doorsteps days apart.

A Weakened Work Force

In a way, one might not expect the hollowing out of Lavumisa's adult population to have much affected its minuscule economy. Unemployment in Swaziland averages 34 percent. There is no shortage of cheap labor to replace a fallen clerk or farm worker.

But the death rate is transforming businesses and the work force, in ways not easily visible.

Peter McIntyre, 66, is one of Lavumisa's real estate baron's and probably its biggest private employer, owner of a grocery store, a liquor store, the gas station and the Lavumisa Hotel. He has lost about a fifth of his 60 workers to AIDS; the latest, a yard worker named Julius, died Oct. 4. Another worker is dying, he said; she begs him daily to look after her five children when she is gone.

Employees like the yard worker are easily replaced. Not so his accountant, who died of AIDS in 2001. Mr. McIntyre's relatives said it took three months to find and train a qualified replacement.